With new map-drawing tools at their disposal, U.S. residents are paying more attention to how congressional lines are drawn than ever, following the release of 2020 Census data.

On a recent Tuesday night, Khyla D. Craine, chair of Delta Sigma Theta’s redistricting committee, led more than 1,000 of her fellow sorority alumnae through how to get involved in one of the most opaque yet contentious touchstones of U.S. democracy.

Legislators were hearing public testimony about where electoral boundaries should be drawn, said Craine, who is also the Michigan Department of State’s deputy legal director. In the fall, map drawers would draft maps using the 2020 census data, which was released on Aug. 12. Anyone — including DST alumnae — could submit comments or alternative maps, which officials in many states had a constitutional obligation to review. The key was to be able to explain exactly how and why district lines should look different.

“We have to make sure we’re knowledgeable about what we’re speaking on,” Craine told viewers, “that we have a very crisp and clear message to our map drawers about what we’re looking for, about how important it is to draw maps that are fair and equitable to communities of color, and what that looks like to us.”

Delta Sigma Theta, which is one of the oldest African-American sororities in the U.S., has been holding monthly “ReDSTricting After Dark” events to spread awareness about what has historically been a shadowy, closed-door ordeal. In that, it is part of a national groundswell of public involvement in carving out the district lines that determine congressional, legislative and local representation for the next 10 years. From North Carolina to Michigan to California, voting rights groups, good government advocates, data crunchers and concerned voices are finding new ways into the fight for fair representation, via informational meetings, mapping contests, testimony workshops and new technologies. The process is receiving significantly more public attention than in past years, observers say.

“Redistricting is an issue that used to put people to sleep or that seemed too abstract or conversely was just about politics,” said Michael Li, senior counsel for the Democracy Program at the Brennan Center for Justice. “No more.”

Among Delta Sigma Theta’s objectives: fending off the gerrymandering that packs communities of color into a smaller number of districts, limiting representation. Other groups have honed in on identifying “communities of interest” — a legal term for groups of people with shared policy concerns that ought to share representation within a district. Fair Count, the Georgia-based census outreach organization founded by former Georgia gubernatorial candidate Stacey Abrams, has been leading “Mapping Mondays” and “Testimony Thursdays” workshops on Zoom, where residents train to draw communities of interest on an online map and share their views with state authorities. The National Black Nonpartisan Redistricting Organization is taking similar steps with voters in Virginia, while Fair Districts PA is focused on training volunteers to tell personal stories of how previous district shapes have failed to represent them.

Some states have actually put members of the public, rather than politicians, into the role of redistricting leaders. The California Citizens Redistricting Commission — a state-appointed board of independent citizen map reviewers created after the 2008 Voters FIRST Act — is holding more than 30 livestream events to gather input about communities that should be kept intact. Between the meetings, email, mail, and an online mapping tool, more than 1,200 Californians have given public comment to date, said Fredy Ceja, the commission’s communications director. A similar commission in Colorado has held dozens of public forums.

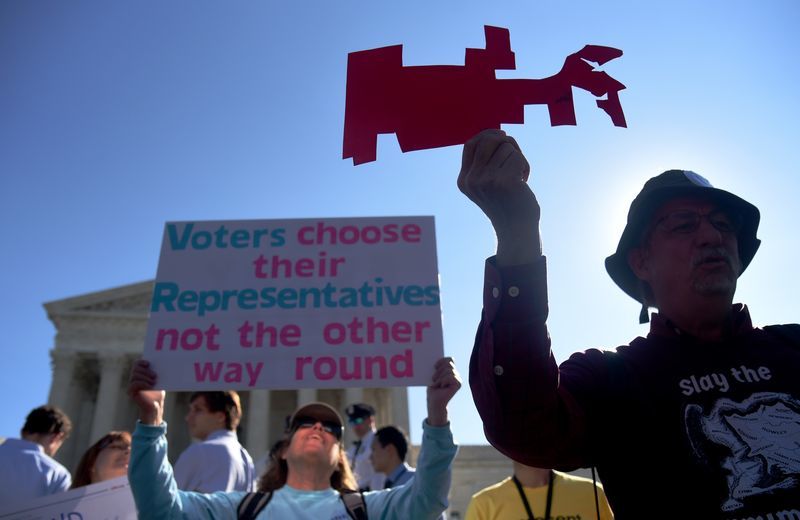

The surge in interest has been fueled by the extreme gerrymandering that came out of the 2010 redistricting cycle. Legislatures in Ohio, Pennsylvania, North Carolina and other states drew congressional district lines in ways that overwhelmingly favored the controlling Republican party. Aided in some cases by powerful new data-processing technology, many district maps sealed victories for right-wing candidates and policies on issues from gun control to health care, despite voter bases that were often more politically competitive.

“In Pennsylvania, the 13-5 Republican advantage was baked in by extreme partisan gerrymandering, no matter what the vote outcome was,” said Carol Kuniholm, co-founder and chair of Fair Districts PA, a nonpartisan reform group. “That reality became obvious when a new, court-ordered map yielded a 9-9 outcome in 2018.” People who’ve spent the last decade feeling like their votes no longer count now want to see change, she said.

Other non-governmental organizations are holding contests where competitors aim to draw competitive, compact and equally populated district maps — or in other cases, maps that appear fair but actually favor a particular party or pack in minority voters, highlighting the potential for deceptive gerrymandering. The Princeton Gerrymandering Project received 130 entries for its Great American Map-Off, which asked mapmakers to try their hand at redistricting Florida, Ohio, Colorado, North Carolina, New York, Illinois and Wisconsin, according to project staff. Seventy-five of the top mapmakers were then recruited to continue creating alternative maps and data analyses alongside a brain trust of academic experts throughout the redistricting process.

One of them is Michael Waxenberg, a technology risk specialist in Pennsylvania who has made a hobby out of district line-drawing since his state’s starkly gerrymandered congressional map was sent to the U.S. Supreme Court in 2018. Since that time, the level of activism behind the issue has grown, he said. Most reform groups do not explicitly align with a particular party. Because Republicans control more state legislatures than Democrats, reform work tends to help Democrats, although gerrymandering is also a Democratic pursuit, as in Maryland’s 2011 congressional map. “The work — the math — speaks for itself in a nonpartisan way,” Waxenberg said.

Mapmaking technology has also made what used to be a black box a much more accessible activity. Open-source map-drawing tools like Dave’s Redistricting and DistrictBuilder enable drawers to quickly configure population and party preference datasets into district maps that fulfill key criteria, while platforms like Representable allow users with less expertise to draw and describe communities of interest. The Campaign Legal Center and the National League of Women Voters are promoting PlanScore, a tool where maps can be uploaded and analyzed for partisan bias based on data dating back to the 1970s. “It’s the flip side to how computers have made gerrymandering worse, because they are also making it more democratic,” said Li at the Brennan Center.

For Delta Sigma Theta, the decision to get involved in redistricting is part of a long social justice tradition, which started when its Howard University founders marched on Washington in 1913 for women’s voting rights, despite the racism they faced from fellow suffragists. Alongside census involvement and voting accessibility, the sorority chose redistricting as a focus for its national social action commission in 2018 largely because of the impacts of the 2010 cycle on voting rights, which became even more pressing after the Supreme Court in 2013 struck down Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act, Craine said. The U.S. Supreme Court’s 2019 ruling that federal courts could not get involved in partisan gerrymandering challenges made it all the more clear that states are on their own.

For Craine, the goal is not only to influence this year’s maps but also to lay groundwork for future redistricting fights. This year, more than 200 DST members have joined volunteer cohorts aimed at scrutinizing redistricting in 47 states and Washington, D.C., while thousands more have been trained to watch over local processes.

“If we can come up with a better map that may have a minority-majority district, or a minority-influential district, that would be a win,” she said. “And as we’re getting involved in 2030, we’ll be able to go even bigger.”

Source: Bloomberg.com